I’d been a lawyer practicing on my own for a decade when my business finally failed. Heating bills and rent reminders sat in stacks beside my door, my socks were visible through my shoes, and my toes were visible through my socks.

Some people believe a legal degree magically attracts wealth, but of course no such magic exists. Friends feel uncharitable toward attorneys, and all of my family members were dead or missing. With an office the size of a shoebox that doubled as my bedroom, finding new clients was rare. Even my typewriter was set to be collected, threatening my ability to earn any future income.

Presently, I sat down at my rickety wooden desk, set my fingers to the old keys with smudged out lettering, and began to type at what I assumed would be my final project as a working man.

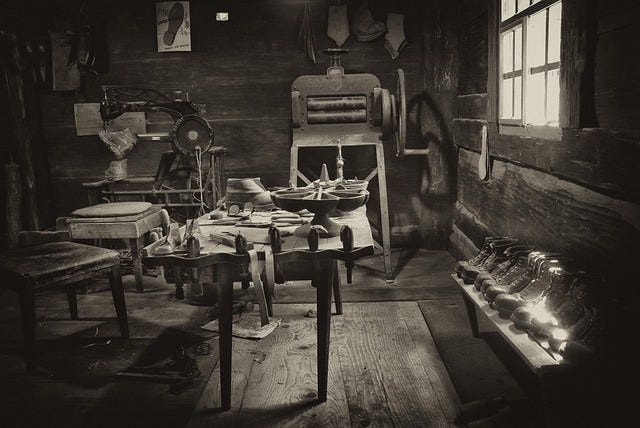

My client — a kind, elderly shoemaker — had hired me to write a memorandum providing a legal analysis of her business plans. I clicked and clattered at my keys, setting out the structure for the memo and a rough description of the facts to consider: she was shifting operations from a plant in Connecticut to New York and would be hiring a pair of employees and a handful of contractors.

To research the legal precedents, I stood and pulled the index of the latest cases and soon found a reasonably good fit. In the case, a Vermont manufacturer of skis had been penalized for failing to maintain certain licenses. I clapped my hands and left a note to complete my analysis in the morning.

With my outline set, I disengaged the typewriter with a click, replaced my chair, and stood above my desk to think for a moment.

The typewriter was scheduled for collection in the afternoon, so if I submitted the work and received payment early tomorrow, I might be able to stay in business for another month. If the business survived, I could focus on finding another client. And to finding something to eat other than the cabbage, and —

I sighed, stepping two paces from my desk over to my small bed. Even if I was paid tomorrow, the best I could hope for was to begin to chip away at my unending series of obligations. I imagined the bills, the rent, the taxes, clumped together and hanging there above my bed like a shadowy, hooded wraith.

My nightly prayer helped to clear my mind, and soon I was wishing for harmony and peace in the world.

The next morning, I was grateful to see my typewriter beside my bed, still in its usual place. I rolled myself standing, stretched my sore back, hunched down over the desk, and fetched a fresh stack of paper to finalize the shoemaker’s memorandum.

Only, I found my stack of white paper was already typed upon.

The memo was written, twenty pages long.

I fell back into my chair, my heart leaping in my chest, my fingers drumming on my thigh. It was cleanly written, italics and commas and case citations in all the right places. The typist had even discovered a new case, more recent and relevant, about boots rather than skis.

Single spaces had been used after sentences rather than my usual custom for double. I scratched at my overgrown and scraggly beard, wondering what matter of magic this had been. Flakes falling from my beard, I was immediately reminded of my need for a razor — which triggered my even greater need for income. With a harrumph, I added my signature to the end of the document, beside where my name had been tidily typed, then left the house and went straight to the local courier to send it to the shoemaking client.

I was scarcely home when my landlord knocked. Someone had called, asking for me, he explained. I’d been putting his number on my stationary ever since my phone line had been shut off. I followed him to his room and picked up the receiver.

“This is brilliant!” an excited voice told me. I could recognize the cobbler woman’s voice.

“I’m glad —”

“The bootmaker case analysis is perfect. This will speed up my expansion, which means I’ll unlock a transfer from my investors. I’m wiring you double your fee right now. Simply brilliant!”

After our call, I looked my landlord in the eye for the first time in months and promised I’d be paying him soon. Back at my desk, I arranged to pay for the typewriter, and the following day, I took calls from two prospective clients, one by recommendation of the cobbler, and a second who referenced my ad in the paper.

“Can I ask which paper?” I asked the new client over my forgiving landlord’s phone. “For Bates Legal Firm? John Bates?”

The caller confirmed he’d seen such an advertisement.

Of course I hadn’t placed one; I hadn’t purchased even a flyer in ages. I shrugged and took on the project.

When I hung up the phone and climbed the steps to my room, I felt a strange emotion overwhelm me. For the very first time in a very long time, I was optimistic. It was as though an iron weight that had been tied around my shoulders and neck had been cut free.

I was now busy. I spent the afternoon researching and crafting outlines for the two new clients’ matters, and had only barely started one before the evening was upon me.

When I went to bed that night, I said my prayers forcefully, encouraged by the day’s events.

And in the morning, I set about to work with fresh courage, but this was unnecessary because both memos had been researched, written, typed and finalized. I signed my name and payment came quickly. And so did new, wanting clients.

And so it went on. What I prepared in the evening was finished in the morning, and my business grew, until one day I found myself grinning for the simple joy of it as I strolled to the mailbox and dropped off a check for the last sum I owed my creditors. That day I purchased a razor and shaved my face, and I took my shoes to the friendly cobbler for repair.

I even called on a woman I’d once dated, a friend from law school whom I hadn’t seen in years. Marilyn’s hair was just as dark and curled as I’d remembered it. When we met at a cafe with waiters and real silverware — a place I’d often passed jealously in my time of poverty — I was wearing a new pocket watch and a suit made of fine material. Marilyn asked with a crinkle in her brow if I’d finally made a change of career.

“You’ve never liked the law, I know,” she noted.

“No I haven’t,” I agreed, “but it was what I had. And now, thank God, I have nothing to worry about.”

Marilyn laughed kindly and my heart jumped at hearing her gentle voice. “And who has helped you make this change?”

I merely smiled in response, even as she made a joke about little green men coming to help me in the night.

Marilyn and I continued seeing one another, her kindness and support a welcome boon in my life. Only after a year of courtship did I reveal the truth to her. While happy for me, still she pushed as she always had since I’d known her; “do you truly like your work?” Do you think you are proficient at it?”

“My love, those questions no longer matter.”

“Then let’s stay up and watch. Let’s see who has been coming to help you — to help us. Shouldn’t we at least be able to thank them?”

I thought the idea over for an evening. Marilyn and I had moved to the apartment across the hall, keeping my old place as an office. I’d replaced my desk with a rich mahogany one and the typewriter with a newer model, one with clear keypads, although I never touched them.

Until now I’d felt too nervous to jinx my good luck, but now that I was comfortable, and at Marilyn’s encouragement —

You’re right,” I agreed. “We have to thank them.”

As the evening grew late, Marilyn and I adjusted the bookshelves to make a hidden space between the desk and the window. There we sat and watched and waited.

When the fine new clock I’d acquired struck midnight, we saw the door to the office open and a hunched figure creep inside and sit before the desk. I felt a vague sense of familiarity at the man’s profile and shaggy appearance, but could not place him. Whoever it was, he was clearly a vagabond, his over-large trousers showing wear, the ribs of his chest visible through the torn cloth he wore as a shirt.

Sickened by the sight of the intruder, I nearly stood to confront him, but Marilyn quietly pulled me back to our place between the furniture.

In our view, the visitor picked up the papers I’d left and scanned them quickly. He slotted the new typewriter’s carriage into place and set to work. Throughout the night he retrieved dozens of books down from the shelves then returned them, pausing only to type at the memos so quickly and efficiently that I couldn’t turn my eyes away. It was sublime to see the way he clattered at those keys and rifled through those pages as though he’d been born for it. The wretch didn’t stop for so much as a glass of water, until suddenly he stopped typing. He set the carriage down and wiped it clean, carefully set my plush leather chair back just so, placed the memos under a golden paperweight, and stepped for the door.

As he paused to turn the knob, I saw his face clearly in the moonlight from the window. He was my brother Theodore. In rags, shoeless. His cheeks empty, his eyes sunken, skinny to the bones, weathered and tired, with a long, shaggy beard, just like I’d once worn. But he was Theodore; I was certain of it.

I hadn’t seen him in years; when we were younger, my brother had gradually started to live his life on the streets, panhandling and begging. Shortly after I’d left for law school, he had taken a trip south of the border and never returned or been heard from since.

Just knowing he was alive spurred a welling of emotions; tears came to my eyes thinking of how terribly I’d ached for him, how our parents had grieved him until their dying days, how they’d so long pestered the police and officials to take action to find him.

Sitting crouched in my office, a desperate need to speak leapt from my chest into my throat, but it encountered there such a torrent of hesitancy, loneliness, fear, excitement, and confusion that I couldn’t speak. My tongue was a leaden slug in my mouth.

I reached out, but Marilyn drew my hand back and held me tight as Theodore closed the door behind him. “You’ll scare him,” she whispered.

We slept not a wink that night, my emotions stealing my mind from me, and Marilyn excited to discuss our discovery.

“There is this joy at seeing my brother,” I explained, “but the confusion at his presence.”

“The wonder of how and why,” Marilyn added.

“Yes — how at all? He has paid down my mortgage,”

“And yet he lives like a beggar.”

“And from where do his legal skills come?”

“It’s Winter,” Marilyn noted. “He must be freezing, wherever it is he lives, skinny and wearing rags and those broken shoes. We have to show our gratitude.”

The next week — after sending out and collecting on my brother’s impeccable work — Marilyn and I went to the shops. Day after day, we picked trim pants to replace his rags, a narrow waist that to befit his slender form, shirts the colors Theodore had loved in his youth, scarves of the softest fabrics. We collected meat pies, wool hats, and blankets. After much deliberation, I also withdrew a sizable sum of money from the bank and tucked it in the pocket of a handsome jacket we’d purchased.

When all of our gifts were ready, we laid our presents on my desk and hid in our place behind the bookcase. At the stroke of midnight, Theodore came scraping in, hunched and shrunken and bearded. At the typewriter, his curled body straightened when he saw not an outline, but the note I had written explaining his gifts, and a short letter expressing our thanks, admiration, and love.

He stared at the note for a long time. And then he showed intense delight, pulling on the jacket, biting from an apple we’d left on the desk. For a time he simply sat and grinned, and then he began to hum. He hummed louder, to a tune, and finally, he sang a song, first under his breath, then loud enough for me to pick up the words:

Now I am a man so fine to see, why should I, longer a lawyer be?

With each verse he repeated I could see the joy within him growing. His mouth broke upward from its sour, frozen place; his posture lengthened; his eyes brightened. Not only did the new clothes fit well, but it seemed his skin and hair and beard — so much like mine — were shining.

Marilyn and I were both in tears as we watched him dance about the office, by the new bookshelf and where the bed used to be. Bundling the gifts in his arms, he skipped and leapt over my chair and past the desk, and danced straight out the door.

From that time forth, he no longer returned. Whether or not Marilyn or I hid in the room, whether or not we provided further gifts, the draft memoranda I left at the desk remained untouched in the morning. The only legal work in that office came from the efforts of my junior hiree, whose skills were no match to those of my talented brother.

Frustrated, I raised the issue with Marilyn.

“I don’t understand it,” I said.

“Understand what?” she asked.

“Why did he leave?”

Marilyn tightened her dark brows in thought. “And why did he come in the first place?”

“And where has he gone?”

We agreed that wherever he now lived, we hoped he was prosperous. We were grateful for his presence, even if he had gone away.

“I could hardly ask for more than what he gave me,” I said with finality., and we stopped speaking of it.

But soon, our hopes and questions turned to more immediate matters; how could I answer the legal questions of a frustrated client; who would arrange the firm’s advertising? Marilyn and I tried to grow the business, and then we tried just to keep it afloat, but all of our prospects slipped through our fingers, just like my brother had.

Still, I remained steadfast that Marilyn and I had made the right decision. I loved Marilyn, her twinkling intelligent eyes, and she proclaimed to love me, even as I was forced to grow a scraggly beard to save on the cost of razors.

In the mirror, I began to take on a similar appearance to Theodore as we’d first seen him. My eyes narrow and hard, my ribs visible and my clothes falling to pieces. I felt like a ship sunk to the bottom of the sea that was beginning to rot.

“My word,” I told Marilyn, wrapping my skinny arms around her shoulders. “At the same time it feels terrible, I can feel a freedom in it.”

“Yes, we are free,” she smiled, encouraging with her eyes.

“Freedom from the guilt of using the work of another.”

The air felt light in my lungs and I wondered at the new life we might build.

Encouraged by Marilyn’s continued coaxing, I resolved that I am not meant to be an attorney.

Our neighbors were generous with food, and though life was difficult, it was also free.

When one day we encountered my old client, the shoemaker, in the bread line, she told us about how her business had failed like ours.

“My customers vanished, slipped through my fingers,” she said with slumped shoulders.

“Where is your factory now?” I inquired. She explained that it was just here in the neighborhood, not two blocks from where Marilyn and I were encamped in my old office.

At night when the moon was hidden and the only light was the crinkle of the stars, Marilyn and I visited the old woman’s workshop. We wore our overused garments and worked together at learning the craft of making shoes, and by the time we slipped out before dawn, we’d finished a simple sandal according to the cobbler’s design.

At home, we worked to build our skills — Marilyn’s intelligence and my newfound excitement combined for a potent combination. After much planning and work, we returned to the cobbler’s shop, night after night, repairing and modifying and building shoes, our spirits soaked through with fascination and wonder. We loved our new life, helping the cobbler by leveraging our God-given abilities.

We watched from afar as the woman grew happy and satisfied, and shared the spoils with us in nightly offerings. She also donated and shared her wealth generously with the community, volunteering her time at a shelter to serve delicious food she’d been taught to make as a girl, providing her own prodigious talents to help those around her.

One night, years later my brother appeared again — in elegant finery, his body healthy, his grin wide, he crept up next to us in the middle of the night at the shoemaker’s work table. He sat with us and hammered the soles of the shoes that Marilyn and I prepared; we worked in silence, wonderfully happy to be in his company, sometimes singing quiet songs as we worked.

Text copyright © 2021 by the author. Illustration by Pixabay, used under license.

About the Author: John (website) lives on an old cattle ranch in Petaluma, CA, where he writes in the mornings, works as an attorney during the day, and tries to keep the coyotes away from the goats in the evenings.

Very nice rethinking of a classic tale